Assessing Questionnaire Validity

Questionnaire surveys are measurement instruments. While scientific measurement instruments measure physical properties like velocity or weight, questionnaire surveys often measure respondents’ self-reported attitudes, opinions or behaviours. They are used frequently in social science to measure what psychologists call constructs.

As constructs are intangible and complex human behaviours or characteristics, they are not well measured by any single question. They are better measured by asking a series of related questions covering different aspects of the construct of interest. The responses to these individual but related questions can then be combined to form a score or scale measure along a continuum.

Reliability and validity

As with scientific measurement instruments, two important qualities of surveys are consistency and accuracy. These are assessed by considering the survey’s reliability and validity.

Following on from our previous blog which looked at approaches to assessing reliability, this blog focusses on ways to assess a survey’s validity.

As with reliability, the validity of a survey can be assessed in a number of different ways and the methods to choose will depend on the survey design and purpose. Often it is desirable to use more than one to facilitate a more rounded judgement of validity.

Validity

Validity is the extent to which an instrument, a survey, measures what it is supposed to measure: validity is an assessment of its accuracy.

How do we assess validity?

Face validity and content validity are two forms of validity that are usually assessed qualitatively. A survey has face validity if, in the view of the respondents, the questions measure what they are intended to measure. A survey has content validity if, in the view of experts (for example, health professionals for patient surveys), the survey contains questions which cover all aspects of the construct being measured.

Face and content validity are subjective opinions of non-experts and experts. Face validity is often seen as the weakest form of validity, and it is usually desirable to establish that your survey has other forms of validity in addition to face and content validity.

Criterion validity is the extent to which the measures derived from the survey relate to other external criteria. These external criteria can either be concurrent or predictive.

Concurrent validity criteria are measured at the same time as the survey, either with questions embedded within the survey, or measures obtained from other sources. It could be how well the measures derived from the survey correlate with another established, validated survey which measures the same construct, or how well a survey measuring affluence correlates with salary or household income.

Often the purpose of a survey is to make an assessment about a situation in the future, say the suitability of a candidate for a job or the likelihood of a student progressing to a higher level of education. Predictive validity criteria are gathered at some point in time after the survey and, for example, workplace performance measures or end of year exam scores are correlated with or regressed on the measures derived from the survey.

If the external criteria is categorical (for example, how well a survey measuring political opinion distinguishes between Conservative and Labour voters), while still criterion validity, how well a survey distinguishes between different groups of respondents is referred to as known-group validity. This could be assessed by comparing the average scores of the different groups of respondents using t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Construct validity is the extent to which the survey measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure, and as such encompasses many, if not all, validity concepts rather than being viewed as a separate definition.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a technique used to assess construct validity. With CFA we state how we believe the questionnaire items are correlated by specifying a theoretical model. Our theoretical model may be based on an earlier exploratory factor analysis (EFA), on previous research or from our own a priori theory. We calculate the statistical likelihood that the data from the questionnaire items fit with this model, thus confirming our theory.

This blog doesn’t provide an introduction to factor analysis, we’ll post an article on this topic in the future. Here we explain how factor analysis is used in the context of validity.

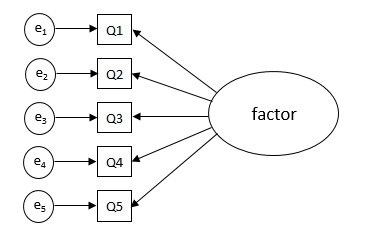

Below is a diagram representing a simple theoretical model.

Here there are five questionnaire items (labelled Q1 to Q5 in the diagram above), each of which is measured with a component of error or uncertainty (labelled e1 to e5). The model hypothesises that an individual’s responses to each of the survey questions is influenced by the underlying latent construct, the factor. The construct is “latent” because it is not directly observed, it is observed or measured through responses to questions related to the construct. For example, respondents with higher levels of self confidence will be more likely to endorse statements such as “I am happy being the centre of attention” or “I feel comfortable talking to people I don’t know“, whereas respondents with lower levels of self-confidence are more likely to disagree with these statements. So respondents’ questionnaire responses are driven by, and correlated with, their underlying characteristic.

This kind of model is known as a factor analysis model. It shows how the correlations between the questionnaire items can be explained by correlations between each questionnaire item and an underlying latent construct, the factor. These correlations are known as factor loadings and are represented by arrows between the latent factor and the questionnaire items.

By fitting the model we can estimate these factor loadings. We then compare the estimates of the factor loadings with their standard errors and calculate the likelihood that these are different from zero, and therefore how much statistical evidence there is to support our hypothesis (that the theoretical factor analysis model fits the data). We can also compare the fit of the model overall with goodness of fit statistics such as the model Chi-squared, the Comparative Fit Index and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Using confirmatory factor analysis we test the extent to which the data from our survey is a good representation of our theoretical understanding of the construct; it tests the extent to which the questionnaire survey measures what it is intended to measure.

Relationship between validity and reliability

While reliability and validity are two different qualities, they are closely related and interconnected. A survey can have high reliability but poor validity. A survey, or any measurement instrument, can accurately measure the wrong thing. For example, a watch that runs 10 minutes fast. However, for a survey, or measurement instrument, to have good validity it must also have high reliability. Without good reliability a survey is not validly measuring what it is intended to measure: it is measuring something else (other constructs or noise). Reliability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for validity.